What is My PhD About?

If I’ve sent you this blog post it’s probably because you’ve asked me something along the lines of, “What’s your PhD in again? Something to do with computers, right?”. Well, my hope is that this little post will explain what I’m trying to do with the next three or so years of my life.

Something to do With Computers Right?

Yep! I’m doing a PhD in Computer Vision, a field of Computer Science that focusses on helping computers and robots ‘see’ the world around them. There are many different approaches and many different problems in Computer Vision, it’s probably one of the largest subfields of Computer Science going. It ranges from the research into autonomous vehicles at Oxford to the amazing work being done at the University of Salford into document digitisation. As it’s an applied field of Computer Science, chances are that you’ve encountered the work produced by the field. That parking camera in your car, Computer Vision. Those digitised census data, Computer Vision.

Okay, so What Bit of Computer Vision?

Good question. I’m currently looking at the problem of ‘scene understanding’. This is actually a pretty broad problem and exists in 2D (the photos you take with your phone), 3D (FaceID uses), and 4D (If FaceID took videos) imagery. However, I’m working in 2D imagery.

The challenge I’m trying to solve is whether we can get a computer to understand a picture, like that taken on a smartphone, in the way you or I would.

Why is that an Important Problem to Solve?

Within 2D scene understanding there are three main tasks that require a humanesque knowledge of a scene: image captioning, visual question answering, and image retrieval.

Image captioning is the challenge of getting a computer to describe a picture using natural language. In order to do this well, the computer must not only identify the objects in the scene but also understand the wider context in which the objects exist. More traditional approaches, such as template-based image captioning systems, fit the detected objects into premade templates. This leads to captions such as: “Image may contain: people playing sports, baseball and stadium” (Facebook Automatic Alt-Text).

More complex approaches, such as those using AI for generating the language, might come up with a caption like “A baseball player swinging a bat” (Microsoft Word Alt-Text Generator). Whilst this is a significant improvement, it hasn’t mentioned the two players behind the batter. Should the system have included them in the caption? Would you have mentioned them? Would your answer to those questions change if you were describing the image to a severely sight impaired (blind) or sight impaired (partially sighted) person? Image captioning isn’t just used as an academic exercise removed from reality; it has real world impact. Companies such as Meta use image captioning across their products to ensure that they are accessible to those with sight impairments.

One of the other tasks I mentioned earlier was visual question answering. This is where a system is developed that allows people to ask a computer about an image (in natural language) and have it answer. This is challenging because the computer must be able to convert your question into something it understands and relate it to the image. It must then figure out the answer and give you a reply in natural language.

The final task, image retrieval, is the task of finding an image based on a natural language description. This is what powers search engines, and it combines not only computer vision but also information retrieval (another very active area of Computer Science research).

So How Are You Going to Solve These Problems?

The short answer is, I’m not going to ‘solve’ them perse. There are a bunch of incredibly smart people working on these problems (the director of AI at Tesla worked on these for his PhD!) and everyone has their own unique approach to tackling them. The Computer Science community like benchmarks. So, we try out our different approaches and then see how they do on the benchmark(s) associated with the problem we work on. Rather than ‘solve’ a problem, Computer Science is full of advancements in the state-of-the-art – the title that goes to the system that currently scores the highest on the benchmarks.

Okay, so How Are You Going to Approach These Problems?

Like everyone else in Computer Science these days, I’m going to be using AI!

The title for my PhD funding is ‘Machine Learning on Graphs’, which means I’m being paid by the EPSRC to research how computers can learn on graphs.

What’s a Graph?

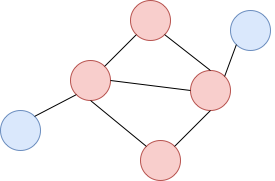

In Computer Science graphs don’t refer to the things Chris Whitty shows us at the Downing Street press conferences, rather they are a representation of how different things interact with one another. Below is a picture of a Computer Science graph.

They are powerful representations that can model lots of things. The circles, nodes, could represent a group of people and the lines, edges, could show who is friends with whom. Lots of information can be stored in a node, but for simplicity, let’s just show people’s favourite colour. Machine learning on graphs revolves around how computers can learn from graph structured data. Information stored in a node is shared and collated with its neighbours. There are several applications for this. The first would be predicting possible links between nodes; in the context of this graph, it would be predicting potential friendships within the group. Another task would be predicting attributes of new nodes; if a new node was attached, what colour would it be?

What’s This Got to do with Computer Vision?

This is the crux of my PhD. Rather than view an image as a collection of pixels in regimented alignment, can we extract higher level information from the pixels and construct a graph? Once we’ve done this, what can we learn from said graph?

The first of those questions has been answered. Yes, it is possible to generate a graph from an image. Nodes are used to represent the objects and relationships between them are represented with the edges. However, the second question is still being researched, and I’m joining in with that research!

Right now, I think that this graph-based approach is the best way of approaching problems such as image captioning, visual question answering, and image retrieval. So much so, I’m going to spend three years of my life trying to make this approach better. You’ll know how well I’ve got on when I write up my thesis at the end of my PhD.